HTTP vs HTTPS

What is HTTPS?

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the protocol over which data (structured text) is transferred between your browser and a website. HTTPS (HTTP Secure) is a more secure version of this transfer protocol, in which all communications between the browser and website are encrypted. It is often used to protect sensitive data in transactions that occur during online banking or shopping. Websites that communicate over https will have urls that begin with https:// rather than http://.

Why?

Many companies are being urged to switch over to HTTPS. While it may seem like everything on the internet changes in the blink of an eye, this switch to HTTPS has been a slow one. For a long time HTTPS was only used within e-commerce sites, on pages that included order forms. It was only recently that usa.gov switched over. However, many have been weary of non-https sites for quite some time now, and Google began to cite HTTPS as a ranking signal for SEO in 2014.

So why the urgency?

When communicating over a regular HTTP connection, all of the data is sent back and forth in plain text, and could be read by anyone who gained access to the connection between your browser and website. Similar to how you’ve learned that we don’t want to store passwords in a database in plain text, it is much safer to encrypt this type of sensitive information. If a user is purchasing something online and fills out an order form containing their credit card information, their financial details are much more easily stolen if they can be read in plain text. With HTTPS, all of these details would be encrypted and a hacker would not be able to decrypt any of the data. In order to decrypt the information, they would also need access to a private key that is stored strictly on the server.

HTTPS applications use one of two secure protocols to encrypt data transfer - SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) or TLS (Transport Layer Security). Both of these protocols use an ‘asymmetric’ Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) system, which uses keys to encrypt and decrypt communications.

Public Key Infrastructure

This strategy of using public and private keys is called a Public Key Infrastructure and is representative of an asymmetric encryption system.

Symmetric vs Asymmetric Encryption

Older, more traditional encryption strategies were symmetric - they would apply a single secret key to any communication message and that key would change or encrypt the content in a particular way. The downfall of this strategy is that it would be very easy for the secret key to end up in the wrong hands when exchanging them over the Internet or over a large network. Anyone who knows the secret key can decrypt communications.

An asymmetric system uses two keys to encrypt communications, a public key and a private key. Anything encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted by the private key and vice-versa. With this key pair, we greatly reduce the risk of someone unauthorized being able to decrypt our communications. Any messages encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the matching private key in the key pair.

The private key should always be hiding on the web server and only accessible to the owner of the key. The public key, on the other hand, will be distributed to anybody who needs to be able to decrypt the information that was encrypted by the private key. (e.g. the browser will need the public key in order to decrypt communications from the website).

You’ve been using different types of key infrastructures since you started programming. Think about how you configured git to work with the web-based GitHub. If you connected over SSH, you may have needed to generate an SSH key to run git commands in your terminal that communicated with github. When we’ve deployed our apps to production on Heroku and integrated with CircleCI, we needed to generate an account-specific Heroku key to link up the two services. While these examples don’t perfectly mirror the PKI system used for SSL, they present a familiar pattern of using keys to provide access to and communicate with a particular service.

CloudFlare built their own PKI infrastructure and documented the process in great detail, if you’d like to learn more about the infrastructure SSL is built on.

SSL & TLS: How Does it Work?

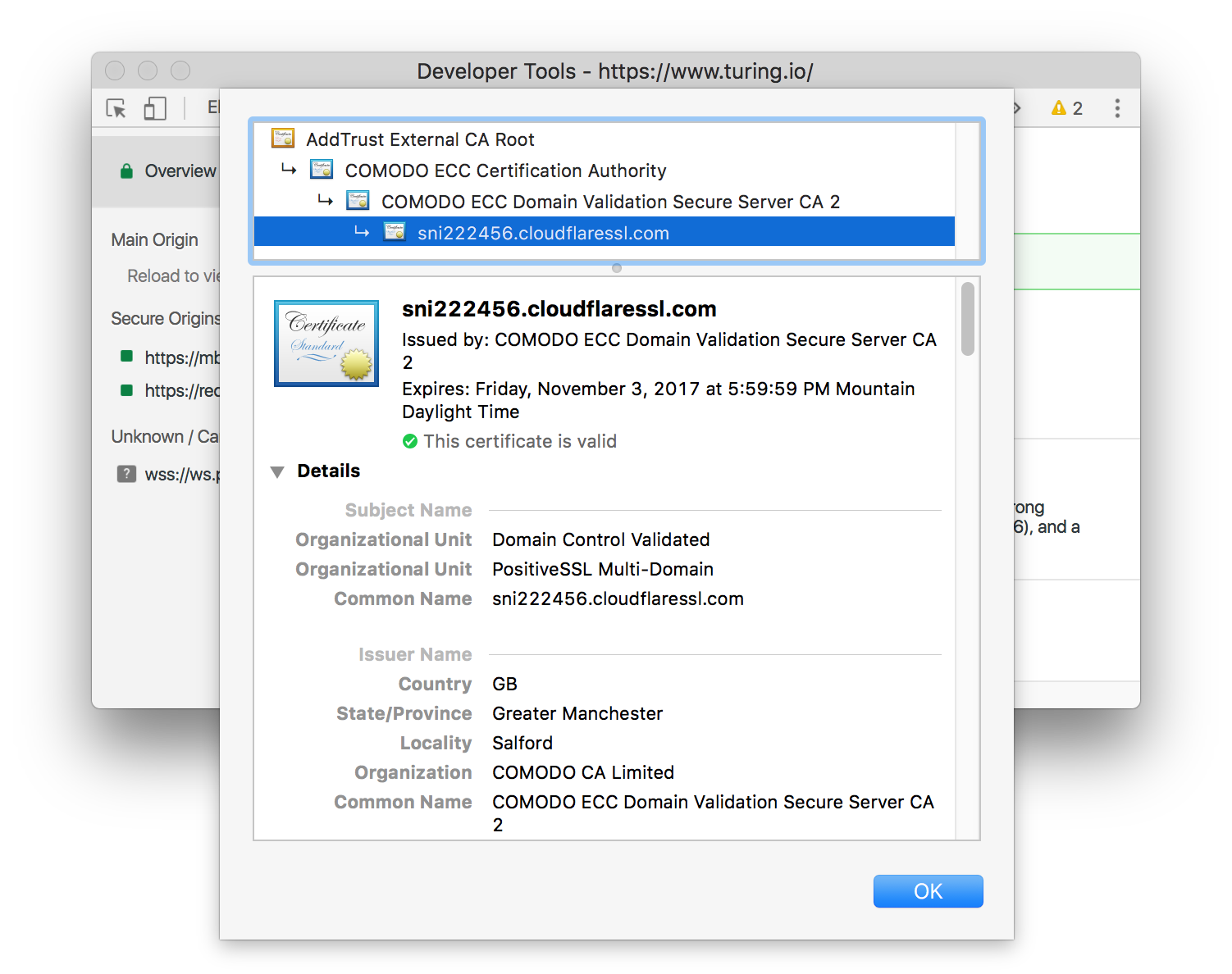

HTTPS applications use one of two secure protocols to encrypt data transfer - SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) or TLS (Transport Layer Security). Both of these protocols use an ‘asymmetric’ Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) system, which uses keys to encrypt and decrypt communications. When you make a request to a site over an HTTPS connection, the website will first send its SSL certificate to your browser. SSL Certificates are issued by trusted, commercial Certificate Authorities (CAs). (Some of these include NameCheap RapidSSL, GoDaddy, and many other hosting providers.) The certificate will typically contain information such as:

- The public key

- A digital signature created by the private key

- Information about who issued the certificate and who it is issued to

- The rights and privileges granted (expiration date/time, hostnames where the certificate is valid, how the certificate can be used)

You can view a site’s SSL certificate by going to the ‘Security’ panel in dev tools and clicking on ‘View Certificate’.

The certificate itself seems to give a lot of information away for free. You might wonder how someone couldn’t decrypt data from the website when given all of the encryption algorithms and certificate data. But remember that you still need access to that private key in order to decrypt anything – think of a typical master lock. We know the algorithm for opening the lock is:

- Turn 3 rotations to the right and stop

- Turn 1 rotation to the left, passing the first number and stopping on the second

- Turn 1 rotation to the right and stop on third number

Even though we know this algorithm and it is well-documented, if we don’t know the 3 numbers to stop on, we won’t be able to open the lock.

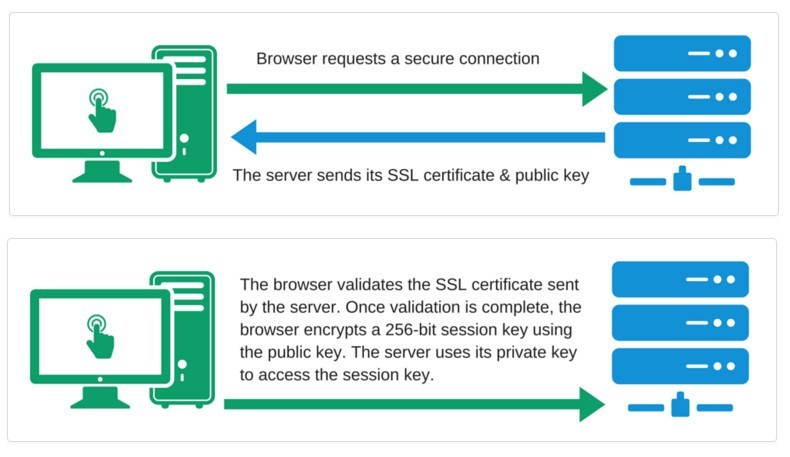

The browser will then validate the SSL certificate based on the information it provides, and encrypt a new session key based on the public key provided. The server will then be able to access this valid session key for future requests. This generation of shared secrets is known as the ‘SSL handshake’. It establishes a uniquely secure connection between your interactions on a website and the data they’re transmitting.

Security indicators in Chrome

You’ll notice that sites running on HTTPS will have a green padlock icon or the word SECURE next to their name in the URL bar of the browser. This signifies to the user that you’re communicating over HTTPS.

However, Chrome is moving toward only indicating when a site is not secured with HTTPS. The thinking goes: the web should be secure and safe by default, and as the majority of sites are now secured with HTTPS, it makes more sense to only indicate a warning when a site is unsecured.

Switching from HTTP to HTTPS

The process for converting an entire site from HTTP to HTTPS is fairly simple, though it does require quite a few steps. The larger your site or application, the more involved this process can get. At a high-level, the transition includes the following processes:

- Purchasing an SSL certificate from your hosting provider about 100/yr)

- Install and configure the SSL certificate - this process can vary depending on your application setup. DigitalOcean has a solid tutorial that can give you some insight into the installation & configuration process

- Ensure a complete backup of your application in its HTTP state exists in case the transition needs to be rolled back for any reason

- Rewrite any hard-coded, internal links within you application from

http://tohttps:// - Redirect any external links you control to

https:// - Implement permanent 301 redirects for each page

- Rewire your application in Google Search Console, Google Analytics, and other tracking tools you might be using

SSL Certifications are not foul-proof

Each security measure we take, like transitioning from HTTP to HTTPS, protects us from very specific security threats - but not all of them. There is no foul-proof solution to all the different ways users can be taken advantage of and data can be compromised. (Think back to JWTs – they allow us to protect an endpoint by requiring authentication, but don’t protect us from any other security threats.)

For example, an EV SSL certificate guarantees that the site you are communicating with is the sit in the address bar. However, because it is fairly easy to obtain an SSL certificate, anyone creating a phishing scheme can easily lure you into a false sense of security by applying one to a site like amazn.com. It would be easy to miss the typo in the URL bar and still believe you are interacting with amazon.com.